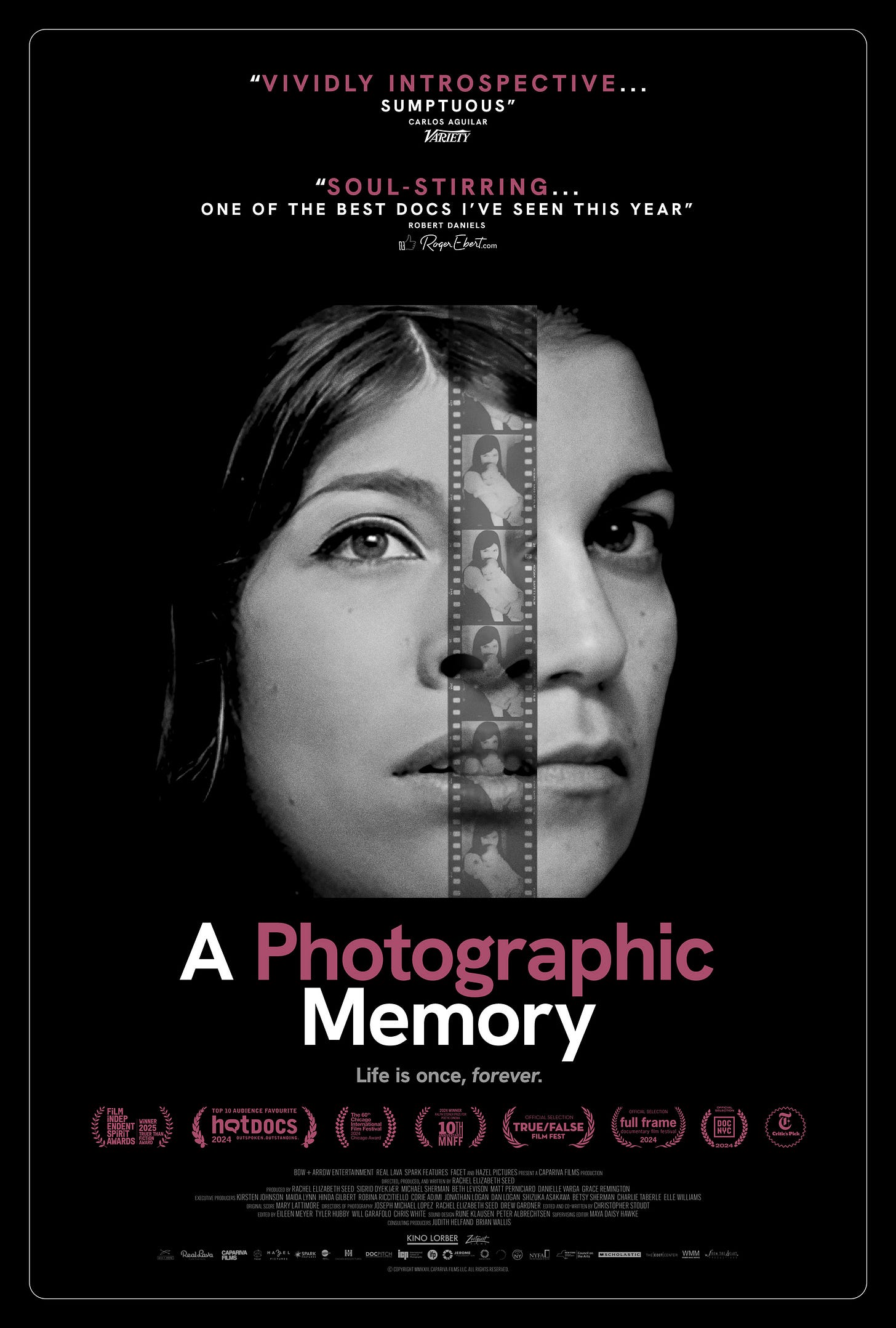

The long road to making “A Photographic Memory” began when Rachel Elizabeth Seed discovered a trove of recorded interviews with world renowned photographers that were conducted by her mother, Sheila Turner Seed. Rachel was embarking on a ten-year journey to better understand her mother who died when Rachel was just eighteen months old.

In the film, we hear interviews with Henri Cartier-Bresson, Bruce Davidson, Cornell Capa and many more greats. Rachel seeks to understand how memory, identity and legacy are constructed.

I learned about the power of what we create as artists and filmmakers and writers. We're leaving such a core part of who we are behind in all this work we're making. That gives me an extra sense of meaning as a maker myself.

Why are we doing this? Can it be preserved? Does it leave something of us when we’re no longer here? There's something comforting about that — there’s a little bit of longevity to it. Even though, at some point, none of us will be remembered anymore, for now it created a sense of wholeness, completion, closure, and a lightness I never felt before. It was a heavy thing to carry for so many years. – Rachel Elizabeth Seed

I spoke with her about the challenges of making such a personal film, including documenting one's most vulnerable moments, the non-linearity of grief and staying the course on a decade-long project, even when it feels impossible. Other topics include handling nude photographs, interviewing exes, casting recreations off Craigslist and fundraising a million-dollar budget.

The film was acquired by Zeitgeist Films in association with Kino Lorber and is screening in theatres across the country, opening at IFC Center andNew Plaza Cinema in New York City on Friday, June 27 with Q&A’s with Rachel and other members of the filmmaking team.

Listen to the whole conversation above or read an edited excerpt below.

On July 15 & 17, The Gotham is hosting a virtual workshop on the essentials for an effective impact campaign for documentary, narrative films, and other content by identifying key skills, goals, finances (including fundraising) and understanding best theories and practices, and understanding how marketing plays a role. Cecilia R. Mejia, a producer and Social Impact Producer, who teaches a version of this class as an adjunct professor at NYU and Hunter College, will guide participants through forging partnerships, creating and implementing successful campaigns, and building a strong marketing plan for the campaign.

Bella: You started life as a photographer, how did you begin making your first film?

Rachel: I actually started as a writer, then got into photography and then filmmaking. It came about because I found my mother's archive of interviews with well-known photographers in the archives at the International Center of Photography, which led to me having a job there overseeing their whole audiovisual collections, digitizing my mother's work. When I first heard her interviews with these photographers, it inspired this film idea.

At that point I had dabbled in filmmaking as a photographer, but I had no ambitions of making a film. Then in one moment, I just remember seeing a flash of “this is a film” in my mind. I had to figure out how to make one, so what began the ten-year journey of making the film was also me learning how to make a film at the same time.

Bella: What was that ten-year process like and what were the biggest challenges over that time?

Rachel: As the producer, the director, the person in the film and the writer, I had to wear many different hats. Some of those hats I had experience with, and some I didn't. It was a lot to balance and carry, both in my personal life and professional life. I had to not only raise our budget, which at the end of the day was over $1,000,000, I also had to emotionally process what I was finding about my mother and translate that into a cinematic experience.

There were so many different levels to the work — emotionally, professionally, creatively. I enjoyed the challenges for the most part and I learned a lot, but it was also very difficult to hold all of that at the same time. I knew that no matter what, I had to finish this beast of a project I had agreed to myself I would complete as I had people investing financially in it and I felt beholden to them to complete it.

Bella: Were there any specific moments where you doubted whether you could actually do it or whether you even wanted to do it?

Rachel: There were many moments where I didn't want to do it and many moments where I didn't know how I could do it, but I always knew I had to finish it. That was my own agreement. It's like, I'm already halfway up Mount Everest, the only way to finish is to move up to the top of the mountain. Even when it got really hard, I had to find resources within myself or outside myself to have the will to keep doing it. It sounds dramatic, but that’s how hard it felt at times.

Bella: What are examples of those resources?

Rachel: Getting back to taking care of myself. When emotionally it became seemingly impossible, I would get into nature, get back into therapy, start writing in a journal, exercise, eat well, sleep. Other resources were fundraising — I had to find the funds to do it. I know filmmakers who use their credit cards to pay for stuff. I always felt like I’m giving every other part of myself, and that’s one place where I draw the line. I had to fundraise and did hundreds of pages of grant writing. I did crowdfunding, Kickstarter. I pitched everywhere from Sundance to Sheffield to IFC. Over a period of years, I built the connections that enabled me to find the resources I needed to finish the film. Also I found strength in surrounding myself with the right producers, the right creatives, which was sometimes a hit-or-miss process over the years as well.

Bella: When you were fundraising, what was the ask that really resonated with all these different funding bodies?

Rachel: If people see that you have conviction, passion, and a clear vision, and that you’re a train that’s moving whether they’re on it or not, I think people are more likely to be a part of something. If you don’t have confidence, if you’re not clear what you’re doing, and you're not helping yourself, people are less likely to come on board.

People could see I was 100% committed and I saw the value in it. As a writer, I could articulate it in a way that people could emotionally resonate with. Once we had a trailer that conveyed that emotion, just having a three-minute piece did a lot of work and slowly enticed people to join along the way. It’s human nature. Once you see more people getting involved, it feels less risky and it snowballs, making it easier for others to sign on.

Bella: This film is really a journey of discovery. What would you say are the most significant discoveries you made while making the film?

Rachel: I was initially driven by this lack that I had because I didn’t know my mother. I didn’t really know where I came from in terms of who she was. I had this longing my whole life. That was the initial driving force. As I found bits and pieces of her — audio, photos, journals, her other work — I started to fill in gaps. That ultimately was a healing process that made me feel whole in a way I never had before.

Reading fourteen journals — in her own words — how she saw herself from age 14 until a month before she died at 42, I got to know her deeply. I almost feel like I might know her better than some people know their living parents. If your parents are alive, you don’t necessarily interview their exes, best friends, bosses, and read their diaries.

Having this knowledge of how she saw herself allowed me to build a relationship with her as a human being, not just as my mother. That was a big gift — to see her flaws, vulnerabilities, strengths, beauty, darkness — all these things at once.

I also started having conversations with my mother about halfway through the process of making the film and I had to figure out how to put that in the film. We isolated hundreds of her questions from the photographer interviews with the help of our assistant editor and put them into a spreadsheet.

I ended up with a list of about 500 questions she asked the photographers. When I had an idea of a conversation I wanted to have with her, I would look and see if any of the questions made sense. We would try them and see if her intonation worked. We tried dozens of different questions and crafted them into a conversation.

Bella: Had AI been more developed while you were making most of the film, do you think you would have experimented more with plugging what audio you had of her into a program that could generate more of her voice?

Rachel: We did explore that about five years ago. Back then it would have been very expensive and probably not very good. But I think ultimately I would have chosen the analog route anyway because I wanted it to be my mom’s real voice saying things she actually said.

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Doc Voices to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.